Has Owen Rubel emailed you, commented on your thread, called you or your co-workers?

Your not alone, feel free to contact me for more information.

This a guest post by Owen Rubel, fellow API architect, and "master of api automation, creator of #iostate, #apichaining". I am working with Owen to better understand API Chaining, and how it can be applied in several projects I am working on. Owen was kind enough to craft this post, to better help me understand is vision, as well as share with my audience. If you want to find out more about Owen, you can follow him on Twiiter @OwenRubel, and visit his Github repository for the more technical side of his work.

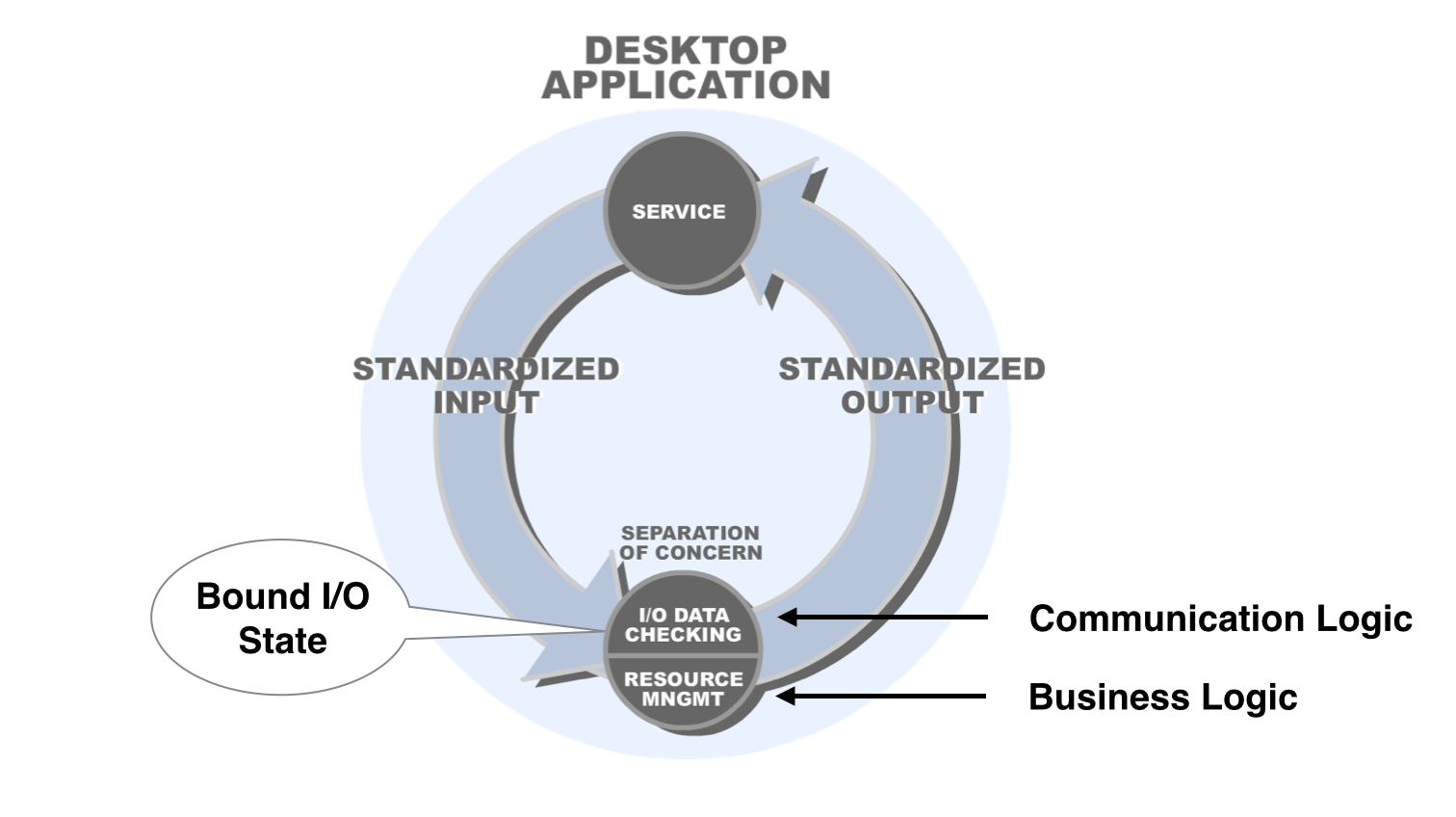

In the early days of API development, the concept of the API was simple. It was designed as an interface to a separation of concern with two sets of functionality: standardized I/O and resource management. This was very convenient when the communication was localized in the application as the bound I/O state for an API call didn't have to be shared with external components. (see fig 1.)

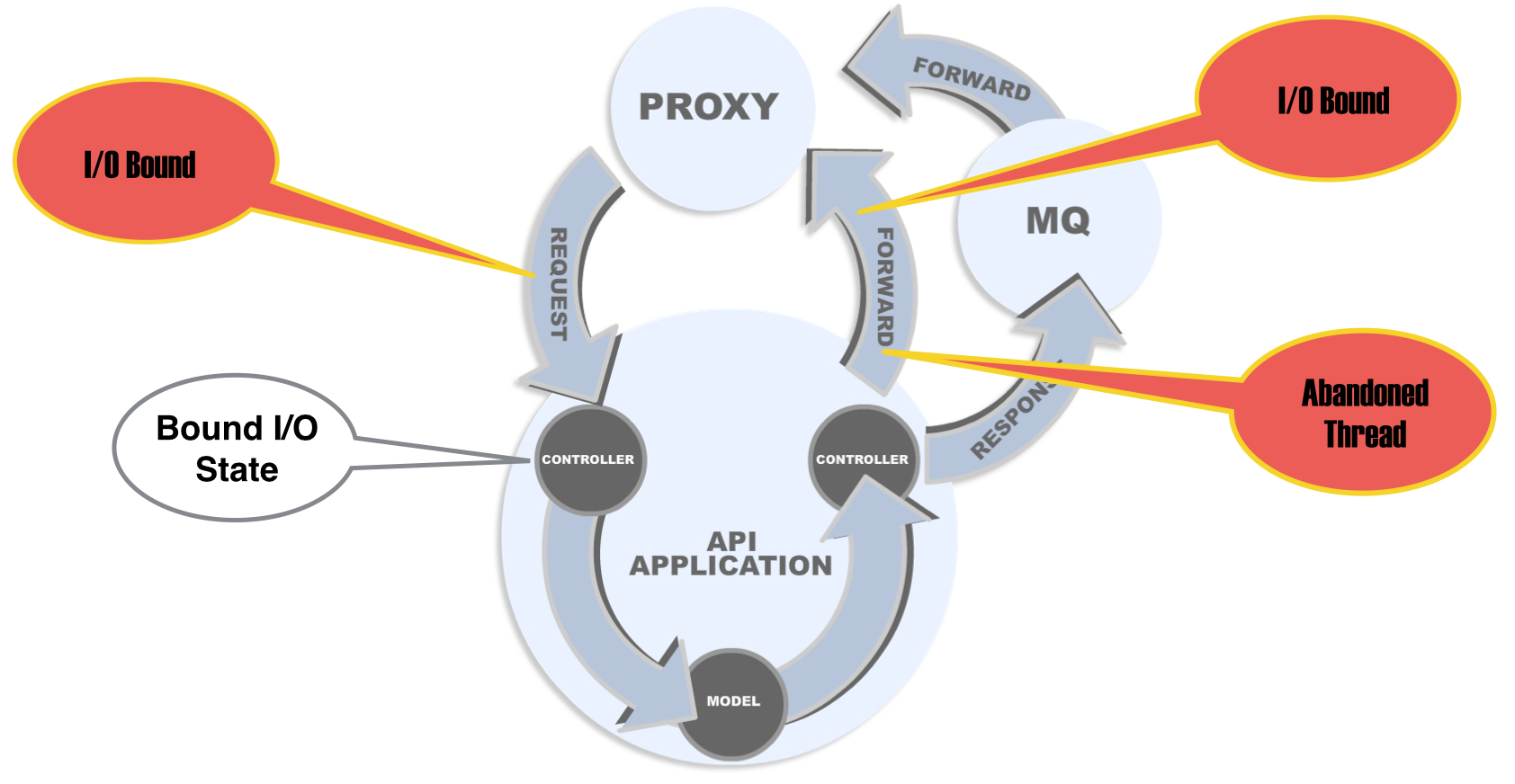

However, as API's were introduced for the web, the internalized I/O functionality associated with the API from the original pattern was gradually extended out with the architecture, and what was once associated with a separation of concern within the API soon needed to be shared across the architecture. This complicated how we built APIs for tooling such as the proxy, API gates, and message queues which now needed to share the I/O state with the application instance.

Original attempts at resolving this issue were to just move all I/O functionality out to the architecture. But this created additional overhead and throughput. For example (see fig 2), if handling security and I/O data checks in the proxy, when doing a forward/redirect in the application AFTER receiving a resource, one would have to send the request to the external architecture to handle security and I/O checks. This would cause the original thread to be abandoned, a new thread to be created, and additional processes to be I/O bound rather than CPU.

Re-engineering the API Pattern

The fundamental flaw in APIs today stems from the original design of the pattern:the original design binds I/O functionality and business logic (as seen in fig 1). This, in turn, binds I/O state to the application so it can't be shared with external architecture, and turns I/O into an architectural cross cutting concern.

To completely resolve this issue, we have to redesign the pattern (and how we develop for it) so the I/O state can be shared and functionality is no longer associated with the resolved endpoint. But how do we accomplish this? For starters, we need to determine where best to handle communications in a framework, some place that has a 'push/pull' mechanism and can effectively 'loopback' and talk to itself. This is commonly known as an 'Interceptor'.

Abstracting The Communication Logic/Data

Every single framework and codebase has something known as an 'Interceptor'. Rails calls them filters, Node.js calls it loopback, and in Grails and Spring we have the HandlerInterceptor. An Interceptor is a common pattern that does precisely what it says: it intercepts the request prior to calling the endpoint and then intercepts the response prior to returning to the client. Why do we care about this?

An Interceptor allows us to put all the pre/post logic associated with the request/response in a common place, therefore creating a communication layer in a framework. And in the case of a web framework, it allows us to create a single threaded loopback. This also gives us the ability to automate communication logic that we have embedded in the 'business logic' such as batching, I/O role checking, and I/O data checking, in turn greatly reducing code.

IO State can be thought of as an architectural schema for APIs. It is the data that defines the current state of the I/O flow stored in a shareable object, the request/response data, roles used for access, version number for matching, and the URI, etc. It is all data separated from functionality that would be useful for resolving, accessing and returning a resource from a given endpoint so it can be used across all architectural components.

Below is an example of I/O State stored for an API call:

The above I/O State tells all pieces of the architecture that when someone calls this domain with the endpoint 'test/show' and version '1', check the following criteria:

- METHOD - request method should be GET

- ROLES - roles that can access this api method; permitAll being 'open access'

- BATCH - roles permitted to call this api method as a batch job

- REQUEST - input data to be sent per respective role; above we expect 'permitAll' to send 'id'

- RESPONSE - output data to be returned per respective role; in the case of role 'USER' we expect [id] but in the case of role 'ADMIN' we expect [id,testdata]

This gives us the ability to have one file for the I/O rules separate from the functionality that can be shared by the API Gateway, proxy, api instances, MQ, and others. And by separating the communication logic from business logic, we can do our method checking, data checking and security checks at the 'pre-Interceptor' and formatting at the 'post-Interceptor'. This reduces Controller code which would look like the following:

To something more like this:

We can now return the same object regardless of ROLE and use IO state to filter data upon exit at the Interceptor...instead of at the controller. This gives us greater controller to check ROLES and input/output at the proxy or the message queue or at any other level of tooling we should need. And because we are returning the same object, we can cache the object, enabling additional speed improvements.

By storing I/O state in a common object and calling it up front, we are able to reject early, reduce processing, reduce the amount of code needed, share IO state, remain more CPU bound and remain nearly 100% stateless.

To be able to share the I/O effectively with the architecture, we need an object that can be loadable by all architectural tooling through a common cache which would hold the I/O state associated with each and every api call. This is what I call the 'apiObject'.

API Chaining : Multiple Requests in a Single Thread

One of the greatest benefits of an Interceptor in conjunction with an I/O state is the ability to do API chaining.

API Chaining is an I/O monad in which multiple API calls can be passed using a single request. A monad works with each call passing the result to the next call in the chain. API chaining builds on this by using the cached I/O state to allow the client to read relationships, build relatable APIs, and send the state for each URI in the chain in one call.

When the API chain is sent, each call is processed and checked, and required data for the call in the chain is sent back through the postInterceptor to the preInterceptor until the end of the chain is reached.

As a request can only have one declared method, the API chain is composed entirely of GET API Calls with ONE unsafe method call (PUT, POST, DELETE). This unsafe method is considered the 'master' method telling it either where to start or where to stop based on what type of chain is declared. For example:

- 'blank chain' - GET > GET > GET > GET

- 'prechain' - POST > GET > GET

- 'postchain' - GET > GET > GET > PUT

A lot of people ask, 'why can't we have the method called in the middle?' This is because it would enable a double call to methods or two unsafe methods in one request. Therefore, we have the unsafe method as the toggle for the start/end of the chain.

A typical chain call looks something like this:

and is called like this:

The API chain is broken out into several pieces:

- data - data is the first set of fields sent

- chain - chain is the api chain object; all data related to the chain is found here

- key - the 'primer' key from first returned set for the next; since you often encode keys in the url or in the dataset, this is a separate place to declare the 'primer' key for the chain

- combine - this is a toggle telling us whether to concatenate results from each call; useful in 'blank chains'

- type - type of chain (i.e., blankchain, prechain, postchain)

- order - the order in which the url's are called; uri's are given as key:val with the 'val' being values sent to next link in chain.

You will also notice the final value in the chain of 'return'. This tells the chain to stop and return, and can be used at any time in the chain for chain branching. Chain branching is a way to stop your chain and branch another chain from it.

Conclusion

The advantages of I/O State, API I/O abstraction, and API chaining can be tremendous, turning every API call into a microservice, as well as reducing your process, your code, and your time to deploy. For example, the use of API chaining in a telecommunications setting on can allow mobile calls to increase their speed by at least 50-75%. Not only does API chaining fix existing issues with the API pattern, but you will also need less tooling, less code, and experience faster delivery and deployment.

For additional documentation and guidelines on API abstraction, please check out the following link: https://github.com/orubel/grails-api-toolkit-docs/wiki/API-Chaining