GraphQL is designed to handle numerous data use cases and and is particularly we suited to adjust to potentially changing data structures and content. But there are situations where the challenge is quite the opposite: we want to be able to expose harmonized and stable schemas and querying mechanisms across disparate data sources or even metadata standards. While I’m still learning about GraphQL, I believe the specification also has the potential to meet such requirements.

Metadata Standards need APIs

One particular use case I have in mind is around metadata standards that often do not come equipped with an API. My focus being on making high quality data available as a service in machine actionable formats and support the FAIR data initiative, I’m referring to specifications such as the Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT), the Data Documentation Initiative (DDI), schema.org, and the likes. As their models can be seen as hierarchical structure of elements and attributes, they seem to be a natural fit for GraphQL.

GraphQL DCAT

As an initial experiment, I decided to start with the Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT) as the standard is fairly light compared to others (only a handful of elements), and also comes with a JSON serialization. I found a nice collection of data catalogs on the U.S. Project Open Data Dashboard which I downloaded for development and testing. Now these are actually based on the DCAT-US flavour of DCAT, which includes a few US specific elements and instructions, but this makes no difference for this proof of concept.

GraphQL Yoga

Of course I also needed a GraphQL server for implementation. I’ve had some initial experience with Hasura, StepZen, and Graphile, but these are designed to work with a SQL server back-ends such as Postgres and not JSON files or databases. So this time I decided to get my hands on Yoga, the open source GraphQL server from The Guild technology stack. My secondary objective was to learn about writing schema definition from scratch, integrating with custom back end data sources, and writing graphQL resolvers with Javascript.

It Works!

This all came together quite nicely. After following the Yoga tutorial, I was able to adjust the schema and code to mirror the DCAT-US specification, and access my test catalogs. As a matter of fact, I added the ability to query across multiple U.S. statistical agencies by wrapping the catalog into a higher level repository entity, which is a feature not supported by DCAT.

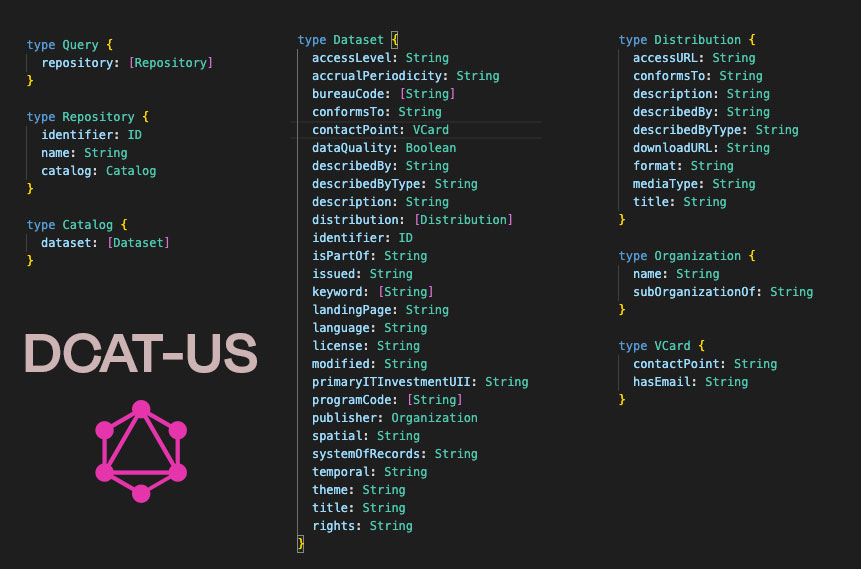

The prototype GraphQL schema definition for DCAT-US looks like this:

My current resolvers’ implementation does not use a database, I basically just load the JSON catalogs in memory and parse. This naturally limits the querying capabilities and scalability, but these are technicalities that can be addressed and were not requirements for this initial investigation.

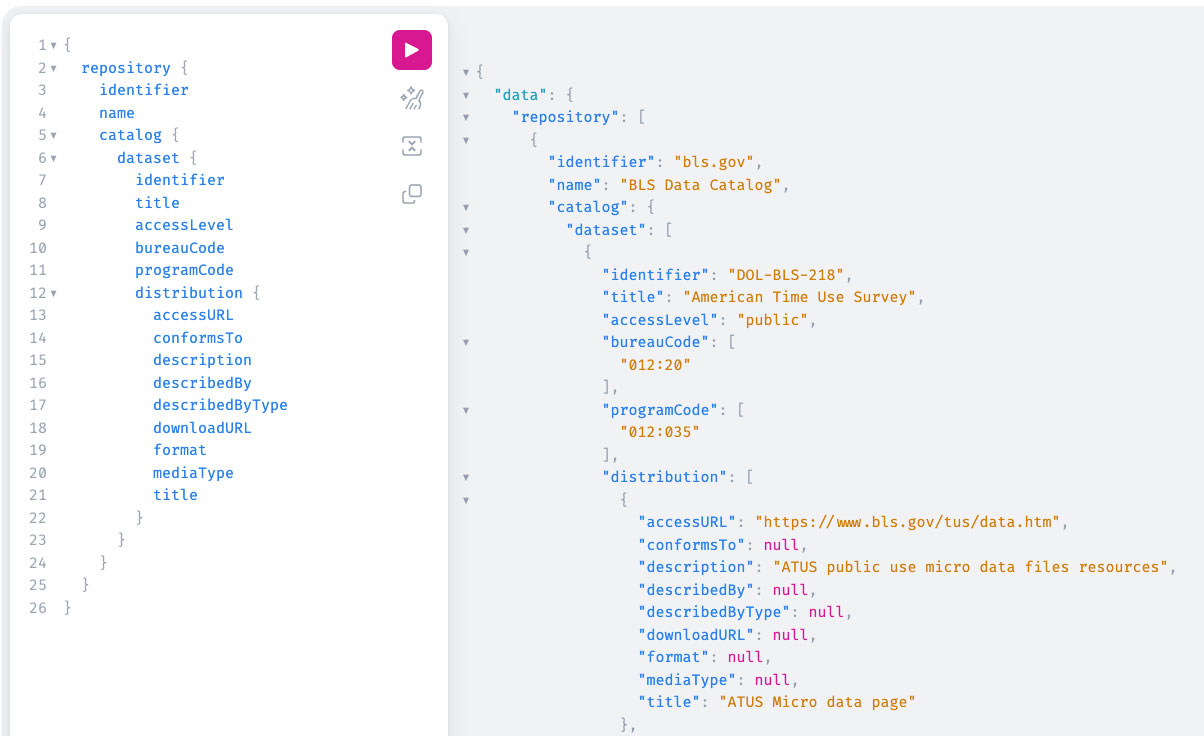

Here is an example of a basic GraphQL query on DCAT-US repositories and results:

Challenges

Moving forward, one technical challenge in translating metadata specifications into GraphQL relates to the inability to namespace or use special characters in field names. For example, we find metadata elements such as @type or @id which cannot be transcribed as is as GraphQL scalars (the @ character cannot be used). Likewise some standards mix elements from multiple namespaces so you may find properties like dc:title or skos:Concept where the abbreviation before the : is a nickname for the namespace. I could stay away from these with DCAT, but something to think about for down the road. I’m confident through that these can be addressed through naming conventions or other mechanisms.

I also found the process or transcribing the model to be a bit painful in terms of writing code, as I needed to pretty much have three versions: the GraphQL schema definition, a TypeScript representation mirroring the types and properties, and then the resolvers. While this makes sense and there are likely not too many ways around this, code generators could reduce the burden and utilities tools like JSON or XML schema converters and JavaScript or Yoga specific tools would be very useful to have.

What next?

While I plan to keep exploring and enhancing this initial DCAT implementation, I’m also very interested next to replicate this with DDI-Codebook (DDI-C), the light version of DDI. One challenge here is the absence of a JSON serialization for DDI-C (it is natively in XML), so some extra translation work will be needed.

Conclusions

This is overall very exciting. promising, and encouraging. To be successful, metadata standards need to be more than just a model and documentation: they must come with tools and APIs. The latter is often absent and GraphQL has the potential to offer a generic solution.